Transition to Exodus

Robert Alter writes in his Translation with Commentary: The Five Books of Moses:

As the long historical narrative of the Five Books of Moses moves from the patriarchs to the Hebrew nation in Egypt, it switches gears. The narrative conventions deployed, from type-scenes and thematic keywords to the treatment of dialogue, remain the same, but the angle from which events are seen and the handling of the characters are notably different. Genesis ended with death, and the distinctly Egyptian mummification, of Joseph. Exodus begins with a listing of the sons of Jacob who came down to Egypt, thus establishing a formal link with the concluding chapters of Genesis in which a more detailed list of the emigrants from Canaan is provided…Instead of the sharply etched individuals who constituted a family in all its explosive dynamics in Genesis, we now have teeming multitudes of Israelites whose spectacular prolificness introduces to the story the perspective of the whole wide world of creation announced at the beginning of Genesis: “And the sons of Israel were fruitful and swarmed and multiplied and grew very vast, and the land [הָאָרֶץ same word as in Genesis] was filled with them” (Exodus 1:7).

Nahum Sarna in Exploring Exodus explains the title:

It is called in English “Exodus,” a title derived originally from the Septuagint, the Greek translation made for the Jewish community of ancient Alexandria in Egypt. It is abbreviated from a fuller title “The Exodus of the Children of Israel from Egypt,” which in turn reflects a Hebrew title current among the communities of the Land of Israel. The most widely used Hebrew name is Sefer Sh’mot (“The Book: Names”), taken from the opening Hebrew words of the book, “These are the names of the sons of Israel.”

Here’s how Sarna connects Exodus to its predecessor Genesis:

The narratives in Genesis focus upon individuals and the fortunes of a single family; they center upon the divine promises of peoplehood and national territory that are vouchsafed to them. In the Book of Exodus, the process of fulfilling those promises is set in motion…God’s commissioning of Moses at the scene of the Burning Bush directs him: “Go and assemble the elders of Israel and say to them: the Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, has appeared to me and said “I have taken note of you [Heb. paqod paqad’ti] and of what is being done to you in Egypt…'” This is a studied echo of Joseph’s dying words “God will surely take notice of you [Heb. paqod yiphqod] and bring you up from this land to the land which He promised on oath to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob.”

In the previous parshiot, the ones of Breishit, we got to know the characters well. In Shmot, we still can learn from the people presented in the parsha, such as the daughter of Pharoah, but I feel more distance. Perhaps we can see the upcoming parshiot as a bridge from character portrayal to nation-building and the giving of the Torah in the middle of the Book of Shmot.

Do you find transitions hard? How do you see the change from the Book of Breishit (Genesis) to the Book of Shmot (Exodus)?

Last year: Best Parsha in the Universe (includes link to a song)

Last year: Best Parsha in the Universe (includes link to a song)

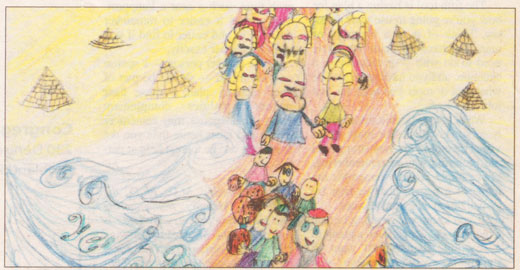

me Ann my camera says

I love the drawing and the parting of the Red Sea is a long remembered bible story to me. The pyramids he included are delightful and they immediately said 'Egypt' to me. Congratulations for such creating a wonderful art work.

Raizy says

Yeah, I really like the pyramids too!

There are certain stories in the Torah that really appeal to kids' imaginations, and the Exodus is usually one of their favorites.

Ilana-Davita says

As a child I loved Exodus.

Wonderful and detailed drawing. Congratulations to your son!

Mottel says

I've always associated the parsha with the times around it. During Shemos, things switch from a a Fall, early winter/Chanukah mode to the deep winter Yud Shvat (the day the Lubavitcher Rebbe took over the Chabad Leadership, and all the Yeshovos travel to New York) is coming mode.

Leora says

Mottel, thanks for the Chabad outlook on the parsha transitions. That's new to me.

Ann, Raizy, Ilana-Davita, glad you like his pic. Wish I could find the original (I posted a newspaper scan).

Mottel says

I wouldn't say it's a Chabad outlook per say (i.e. one based on Chabad Philosophy) - though it could be tied to one . . . it's more my outlook, seen through the frame of the Chabad Calandar.

Mrs. S. says

Nice picture!

The first article in this newsletter - http://www.torahmitzion.org/pub/parsha/shmot.pdf - presents a similar idea. Basically, the article says that Breishit is a Book of individuals. Shmot, in contrast, is about the Jewish People as a nation. However, the two Books are connected, and Shmot is even considered to be the "second stage of Creation".

The Jewish Side says

Very nice drawing by your son.

I liked the last connection, that's a good transition.

And I see what you mean about the difference, Bereishis has more fun stories. Sefer Shemos will have more about laws.

Please leave a comment! I love to hear from you.